Old News

Old News is a page that remembers past events of importance to Morganians.

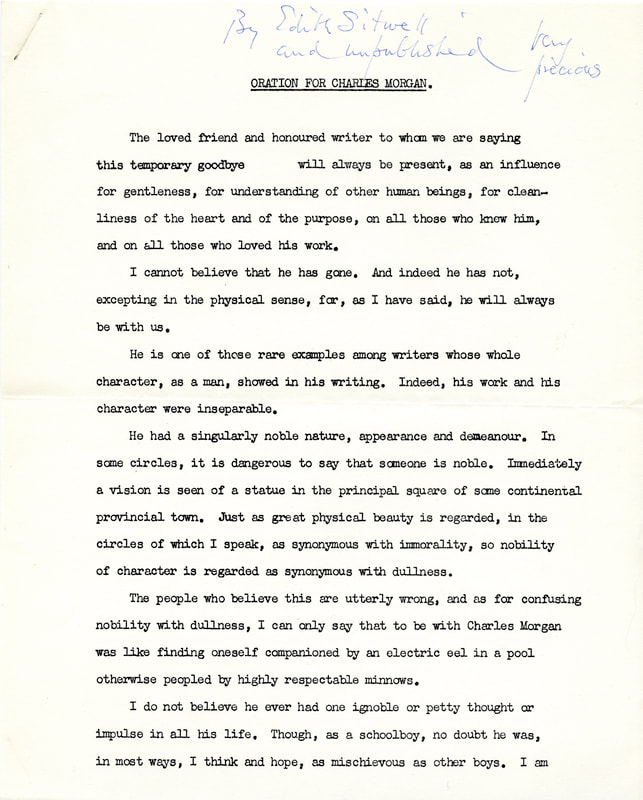

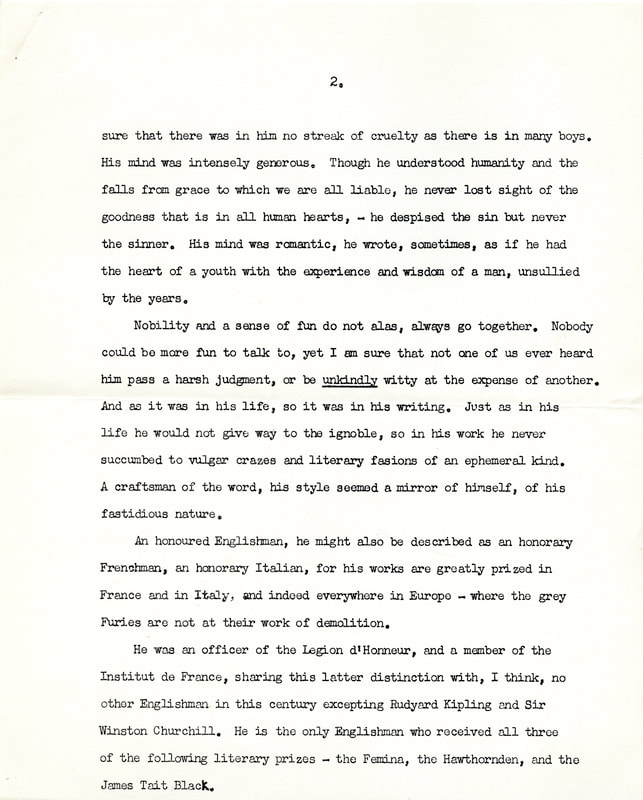

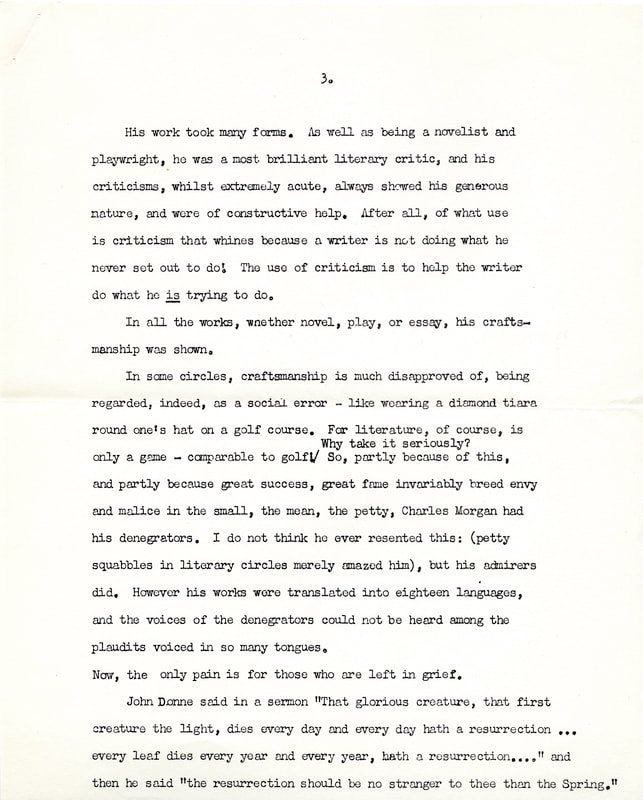

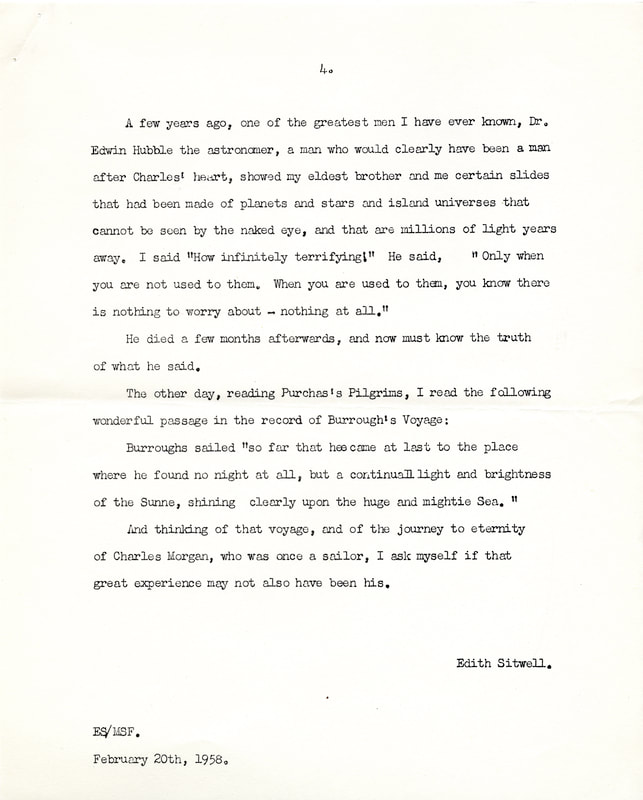

The Funeral Oration at CM's memorial service

As Morganians know, CM was buried in Gunnersbury Cemetery after his death on February 6, 1958. A memorial service was held for him on February 20 in St Margaret's Church, Westminster. At this service, the funeral oration was given by Dame Edith Sitwell, a major poet and CM's friend. This oration has never before been published, and we are grateful to the University of Delaware for having provided us with a scan of Sitwell's original typescript, and to the Sitwell Estate for permission to publish it here. Sitwell's description, and appreciation, of CM is particularly fascinating in view of the often negative view of him prevailing at the time. TO read the text, click on each image in turn.

Edith Sitwell

Sword of honour

It was thrilling to discover, on the website of the French radio station France Culture, a retransmission (in February 2015) of their programme of 27 October 1949, featuring the presentation of the French Academy's sword of honour to Charles Morgan. In this 20-minute broadcast we hear, after the announcer, first the presentation speech by French novelist Georges Duhamel, then the magnificent speech, in impeccable French, by CLM himself, and finally a description and explanation of the sword's design by René Lalou, one of Morgan's greatest friends and academic admirers in France. Here is the embedding code for the broadcast: <iframe src="https://www.franceculture.fr/player/export-reecouter?content=7567fac4-aece-11e4-adec-005056a87c89" width="481" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" height="137"></iframe>. And the URL: https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/la-nuit-revee-de/remise-de-lepee-dacademicien-charles-morgan. NB: See the "Gallery" page for photographs of both the sword and its presentation by Duhamel.

A Powerful Presence

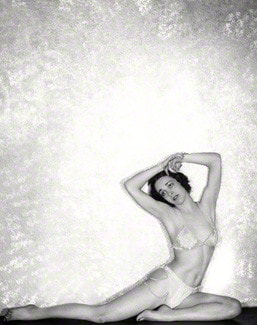

Rawlings as Salome (1931)

Rawlings as Salome (1931)

- As most Morgan readers know, actress Margaret Rawlings was important in his life, not least because it was for her that he wrote The Flashing Stream. So it seemed interesting to publish here the Independent's 1996 obituary of her.

What became of the tragediennes who used to enthrall us in the Greeks, Shakespeare or Webster? Margaret Rawlings was probably the last, and somehow one of the loneliest. She made her own translation of Racine's Phedre, and staged it, after disappointing herself in an earlier one. She was apt to erupt as Jocasta in Sophocles or as Helen in The Trojan Women, somewhat in the spirit of that other and even finer tragedienne, Sybil Thorndike - and, as often as not, in the provinces.The English playgoer likes to keep his tragedies at a distance; Margaret Rawlings liked to come face to face with them. Anyone who saw such confrontations in the 1940s - Lady Macbeth, for example, to Alec Clunes's Macbeth, or Vittoria Corombona in The White Devil to Robert Helpmann's Flamineo, will have had a taste of her quality.

Mind you, she had been other things than tragic. No actress can perpetuate tragedy throughout a stage career as long as hers - 1927-83 - without stooping. Consider her Salome (Gate Theatre, 1931) which set the town alight with its dance of the seven veils. People fainted as she danced.

Has there been anything as erotic since? I speak from reports, of course, of Ninette de Valois' choreography as well as of the performance. It made her name. But Rawlings was not only in the name-making business. She also had dramatic ambition. That was obvious from the word go.

The daughter of a clergyman who ran an English school in Japan, she went to Oxford High School and Lady Margaret Hall, and did her training for the stage with a once-famous company which did nothing but tour the plays of Bernard Shaw.

Rawlings also toured Canada and the United States with Maurice Colbourne's largely Shavian company; and after a success on Broadway in a play abut the Irish leader Parnell she came back to the Gate as its star - Katie O'Shea. It may not have been much of a play, but Rawlings "forced some red blood into the play's white arteries" and a transfer to the West End (New, now Albery, 1936) established her.

Meanwhile, though, she had caught the town's fancy as Charmian in a disastrous West End revival of Antony and Cleopatra. Inadvertently, of course. The Cleopatra was Eugenia Leontovich, the Russo-American star of Tovarich, at dramatic sea as Cleopatra because of her garbled English.

No one joked about Rawlings, however. When Cleopatra at last expired, a palace guard turned to her and said: "Charmian, is this well done?" In a sonorous voice, Rawlings spoke with some authority: "It is well done, and fitting for a princess descended of so many royal kings."

Whereat the long-suffering audience suddenly realised how much more fitting Rawlings would have been as Cleopatra. As James Agate put it: "The cleverest thing about her Charmian was that she refrained from wiping Cleopatra off the stage until she was dead."

Rawlings never played Cleopatra, but she did play Lady Macbeth for the Oxford University Dramatic Society - it was the fashion then for West End actresses to act occasionally for the Ouds - and Helen in Euripides' The Trojan Women (Adelphi, 1937), which Lewis Casson revived for his wife Sybil Thorndike (as Hecuba) and daughter Ann Casson (as Cassandra).

Rawlings was in her element. She was also in love with Charles Morgan, the novelist and chief drama critic of the Times who wrote his first play for her, The Flashing Stream (Lyric, 1939). It was a typically highbrow study of platonic passion between two mathematicians working on a secret new flying torpedo to save England from aerial attack - and work must come before sex.

The play was a success and transferred to Broadway. Rawlings was praised on all sides for her emotional and spiritual integrity. The dramatic point was that the couple were not cold by nature but passionate and sexually experienced (and the point for gossips was that the author and his leading lady were in love and that that year Rawlings and her first husband, the actor Gabriel Toyne, divorced).

Already busy, Rawlings found herself more in demand than ever, if not for tragedy then for comedy (Pygmalion, A House in the Square, Gielgud's revival of Dear Brutus, Gwendolen in The Importance of Being Earnest).

Then came her wartime marriage to Sir Robert Barlow of Metal Box, and several chances to return to tragic vein. Although she seemed strangely ill at ease at Covent Garden as Titania in Purcell's masque The Fairy Queen (1946), her Vittoria Corombona to Robert Helpmann's Flamineo in The White Devil was unforgettable.

In the great trial scene she cut a striking figure on the small stage of the Duchess Theatre - her ivory skin and flowing black hair like ivory starred with jet. The young Kenneth Tynan decided it was the most tragic acting he had seen in a woman - though he had seen Peggy Ashcroft's Duchess of Malfi a few seasons earlier:

She is loud, demonstratively plangent and convincingly voluptuous: a plump, pallid nymphomaniac. And such control! In the great trial scene she eschewed pathos and gave us in its stead anger, mettlesome and impetuous. A stalwart piece of rhetoric and beautifully spoken.

Michael Redgrave used to say that the history of the British stage was the history of first nights when all actors are judged and some (like Redgrave) seldom at their best. It was so with Rawlings.

Three years later Alec Clunes's Macbeth at the Arts Theatre did not create a sensation: but when one critic, Audrey Williamson, saw the production at the end of its three-week run it was different, especially Rawlings as Lady M.

As the enslaved Zabrina in Tyrone Guthrie's 1951 Old Vic staging of Tamburlaine the Great, with Donald Wolfit in the title-role, Rawlings became aware of Wolfit's little upstaging tricks, if he happened not to be in the limelight. Exasperated, she told him: "Donald, if you do that again I shall rattle my chains all through your long speech."

Rawlings kept on acting for another 30 years - in Shakespeare (Gertrude in Hamlet), Shaw (Lysistrata to Noel Coward's King Magnus), Ibsen (John Gabriel Borkman), Chekhov (Uncle Vanya) and Wilde (Lord Arthur Saville's Crime) and in the cinema and on television.

But Racine's Phedre was probably her favourite role. She made a translation of it for herself which I saw on the first night at Oxford Playhouse (1968) with Michael Gough as Theseus. Now I wish I had returned later in the run.

In the 1970s she undertook at the age of 72 the long solo part of Empress Eugenie (Mayfair and Vaudeville, Cologne, Pitlochry, Charleston . . .), a one-woman show about the extravagant wife of Emperor Napoleon III of France, a performance rich in variety of mood, pace, inflexion and salty humour.

Adam Benedick

Margaret Rawlings, actress: born Osaka, Japan 5 June 1906; married 1927 Gabriel Toyne (marriage dissolved 1938), 1942 Robert Barlow (Kt 1943, died 1976; one daughter); died Wendover, Buckinghamshire 19 May 1996.

- Morgan's posthumously-published The Writer and his World (Macmillan 1960) received this on the whole perceptive and positive review from the actor and writer Robert Speaight. Speaight, a convert to Roman Catholicism, published it in the Catholic journal The Tablet on October 39 of that year. He is, we feel, a little unjust to the novels between The Fountain and A Breeze of Morning; but his characterisation of CM as a "spirituel" in the French sense and as a romantic in the English sense is well seen and well put.

CHARLES MORGAN The Writer and His World. By CHARLES MORGAN. Macmillan. 21s.

In a recent lecture on Charles Du Bos, Gabriel Marcel spoke of Du Bos's great admiration for Charles Morgan, and then added, "I am not sure that he was wrong." He went on to emphasise what his listeners probably knew already—that Morgan was far more highly esteemed in France than he was in England. He was a member of the Institut, and Paul Valéry had written a Preface to The Voyage. Morgan, who was a passionate Francophile, could hardly have asked for more. Yet he did ask for more, being also a passionately patriotic Englishman, and he suffered a good deal from the denigration of his English critics. In 1932, The Fountain had been hailed as a masterpiece, and the subsequent reversals of critical opinion were not only to be explained by the inferiority of Morgan's later novels, A Breeze of Morning perhaps excepted. Time and taste had cruelly passed him by ; he was himself hostile to the literary influences then in vogue ; and a writer who set himself up, in the early 'forties, as a porte-parole for Conservatism and Free Enterprise was asking for what he got.

I remember going back to his house one night in the company of Michel St. Denis and we talked far into the small hours. He was an excellent conversationalist. As we left, St. Denis remarked to me, not at all unsympathetically, "C'est fou ce qu'il est romantique." Morgan's romanticism was the key to his opinions and his personality. For him, the exaltations of feeling were an absolute. When Eric Gill had finished reading The Fountain, he observed, "What I want to know is—what happened to the baby?" But of babies, needless to say, there were none. Morgan's treatment of the love story is not brought into question by this collection of his essays, but how good a critic he could be is shown by his study of Turgenev's treatment of the same subject. Turgenev was one of his gods—and that is a shrine where no one need be ashamed to 'bow the knee. But he was principally concerned with the situation of the writer in a world obsessed by ideologies. The obsessions are a good deal less violent now than they were when these lectures were given, and in many places Morgan will seem to be flogging a dead horse. In the same way writers whom no reputable critic would admit to reading fifteen years ago, have now become quite respectable. Mr. Eliot's commendation of Kipling had the effect of the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact. But in pleading for the independence of literature, Morgan does not always distinguish between man the maker and man the moral being. He admits that both in war and peace the writer has certain obligations as a citizen, but when he writes that, "there should be no restraint of writing on moral or religious grounds, for this is to trespass on "la vie interieure," the pornographer is entitled to claim an immunity which few, even in a liberal and indifferentist society, will be prepared to grant him. People who attack the principle of censorship are generally attacking the practice of censors, for even the widest latitude of the law in these matters constitutes a form of censorship. Morgan's plea for the rights of the imagination is generous and eloquently argued, but it needs to be balanced by Maritain's warning that "it is a deadly error to look to art for the supra-substantial nourishment of man." Maritain has developed this idea with exemplary precision in a recent essay, The Responsibility of the Artist.

Charles Morgan was a spirituel in the sense that Charles Du Bos would have used the word, and an homme de lettres in a sense that is still more fashionable in France than it is in England. His kinship—though he was never quite committed to Christian orthodoxy—was with the great Anglicans of the seventeenth century. For all his sympathy with French culture, he was a very deep and very typical Englishman. He was a man for whom little existed 'between the Greeks "and the Renaissance. He could be moved to the depths of his being by a Correggio; he would not have been so moved by a Cimabue. His humanism, in its strength and its limitations, is well illustrated by these posthumous papers, although it is a pity the publishers did not include his admirable Oration to the Saintsbury Club. Their style is disciplined, lucid, incisive and urbane, and they do much to confirm the tribute paid to him after his death by Dame Edith Sitwell. This, too, might well have been included by way of envoi, for it did much to redress a balance which had been tipped unjustly. He was a man of inflexible standards and deep, unswerving fidelities. ROBERT SPEAIGHT.

- In 1941, Morgan's short novel The Empty Room appeared, both in England, very much at war, and in America, not yet engaged in World War Two and very much divided on the subject. It seemed interesting, then, to reprint here an American impression of the novel, printed in the influential Saturday Review, then edited by Norman Cousins. The review is by Millen Brand, a 35-year old novelist and teacher of writing at New York University, who later was much engaged in the civil rights movement. Reading it today we can both see the curiously ideological/philosophical emphasis and reflect on the date of its appearance, just three weeks before Pearl Harbor. The oddest thing about it seems its neglect of Henry Rydal, whose philosophy of lasting values was surely as important in the England of 1941 as his wife's and Richard Cannock's.

From the Saturday Review, November 15, 1941:

THE EMPTY ROOM. By Charles Morgan. New York: The Macmillan Co. 1941. 164 pp. $2.

Reviewed by Millen Brand

There have been written lately a number of important novels about England, and some of the most interesting have been written with a degree of American perspective. “The Empty Room,” ostensibly about people making a contribution in a warring world, more directly than most says what the feeling of the English-speaking democracies is.

The contribution Morgan’s characters are making – the improvement of gunsights or the statutory preparation for peace – is not so important as the awareness growing in them of the need of a changed emotion. That the earth must become alive again. Every good person – and almost all are good under the essential light – asks what is to come of this war, and how we are to go on. “Last time,” Morgan writes, “the deep reserves of Victorian prosperity had held together the wreck of the old world. Now, for good or evil, that was gone: there would be no going back – in that sense, no reconstruction.” And he says there must be “something new.” His novel is the effort to find it. There is the suggestion, too, that in finding it an important instrument will be found for winning the war.

There has been until recently perhaps, in the Western democracies, a too unbounded optimism, and easy belief that humanity is destined to go steadily forward, with its stock of accumulated physical techniques. That leaders and peoples can be counted on to “act right” at the end. But there has always been, like a seed of death, the possibility of retrogression – and it is now that with an approaching final seriousness we see it and know there must be either a “new” future, or an incalculable delay, a long era of suffering, slavery, and human ugliness. And the writer, who is, or should be, like somebody talking with the ordinary people of this world, must express the crisis. Try to give it its real form, so that it can be seen. This is his great task, to see outward through individuals to the living whole, and to give others that sight.

The phase Morgan has chosen for the recognition of crisis is discouragement, separation. Two of his characters, Richard and Mrs Rydal, find the apparent solution of life in withdrawing, believing that their attachment to other human beings will do more harm than good. Both are persuaded finally that “disillusions” are the proving of love and that they have objectively their right to a place in the close center of life. With this personal assertion of values, the direction is suggested in which we have to move to make strong the unity against human degradation and despair, against “imaginations and powers of evil.” That is, I want to believe, the central statement of the book.

But in a book of this brevity, almost every word is important, it is important enough, of course, in any book. And there are shadings in this book, conscious or not, which detract from its statement. At intervals in the book another book is quoted as a kind of commentary and explanation – and is so quoted in the climactic scene. And the end of the quote is this, “God is with all, with the coarse and dull as with the refined and pure, but he draws them by different means – those by terror, these by love.” This statement has a specious eloquence within the scene, but is at variance with the profoundly egalitarian spirit of true Christianity, and with the spirit of democracy itself. None are drawn by terror, all by love.

I mention this because the very unity and joining together of life which is the strength of every real movement against oppression and which this book favors must not be flawed by divisions. Even unconscious or momentary. “The Empty Room,” with a dependence on the supernatural, the ghostly, and a quoting of a selective God for its emotional score, defeats to that extent the great main intention. It shows something less than full understanding of the representative human and the mechanics of change. But the main intention stands, and it is sufficiently realized for the book to be honored for it.

- In the first volume of Malcolm Muggeridge's memoirs, The Green Stick (1972), he remembers his attempts at writing for the theatre. The following passage has a wonderful Morgan-related finish.

I struggled on with my own writing, fitfully but ardently. To my great surprise and delight, it was finally arranged that my play Three Flats was to be produced by the Stage Society. The producer was Matthew Forsyth, and I note in the case several names that afterwards became well known -- Barry K. Barnes, Dorice Fordred, Mary Hinton, Margaret Yarde; among the extras, Anthony Quayle. I went up to London for a dress rehearsal, and sat beside FOrsyth, but was too overwhelmed to say anything much. The play did not seem to be by me . . . . I went with Kitty and my father and mother to the Sunday evening production at the Prince of Wales Theatre. It was an occasion of delirious happiness; there were shouts for the author, and I took a curtain with the cast. My father's pleasure was a great satisfaction to me, and I hope it offset at least some of his disappointments. His eyes were shining. I still had the feeling, though, that the play was by someone else; even when I read the notices, which were reasonably encouraging, especially The Times, whose dramatic critic wrote (I quote from a faded cutting pasted in a scrapbook): 'All is vain, all is scattered and seemingly unrelated, all is at once sad and absurd. What is the unifying cause and truth? The author asks his questions with skill and sympathy, pointing it with faultless observation, that he never permits to become shrill . . . In brief, a play distinguished by the sureness of its detail and the economy of its writing.' I read those words over a good many times at breakfast on the Monday morning. Subsequently I learned that the writer of the piece was Charles Morgan. There is always a catch in everything.

This strikes me as being as good an example of biting the hand that fed one as I can remember.

- Trawling the Web can occasionally net an interesting catch. An example is the following review of Portrait in a Mirror, which appeared in The Spectator on February 2, 1929. For a brief review, it now appears strikingly clear and accurate in its judgement:

PORTRAIT IN A MIRROR. By Charles Morgan. (Macmillan. 7s. 6d.)

Portrait in a Mirror is a great book and a beautiful one. In it Mr. Morgan has raised an altar to first love, and his craftsmanship is exquisite. The story is simple, as befits the theme, and is told in the first person by an artist who looks back on the days of his youth. In 1875 Nigel Frew, aged eighteen, went to stay in a country house; where he met with a girl little older than himself, who was engaged to an eligible young man. Nigel fell in love with her at once, and very early in his love we are given the keynote of the book. She asks, “Is it me you love or just your idea of me ?" He tried to paint her portrait, but achieved nothing but sketches of her hands, her hair, her throat. "It was as an artist not as a man that I wanted then to possess her, and to possess in her beauty itself of which she had become representative."

Time went on. Clare, the girl, became a wife and the boy pursued his art. After some years they met again, and each of them tried to rediscover love's first pattern. But as Clare said to him, "Your love was too soon, mine too late. It's as if two people with different languages were to learn to speak to each other only after their secrets had become meaningless." The consummation of the love which had begun for the boy at a time when dew enchanted the apple of his Eden was as unsatisfying as Dead Sea fruit. He desired the girl whose image he had cast on the mirror of his own love ; she desired the boy who had first seen that image, and neither could find the other who had no existence in the flesh.

To have sustained such a sentiment, as Mr. Morgan has done, without trace of sentimentality is a very great achievement. Some may not agree with his point of view, but as he says, "An artist may not be all-knowing, but of his own vision he may not remain in doubt." The author is in no doubt ; his sincerity and his fearless sentiment gain value by his restraint. His work throughout the book is brilliant, mature and lovely, and deserves grateful recognition.

- Our attention was recently drawn to a review by the great critic John Bayley (husband of Iris Murdoch) of the 1984 Boydell reissue of The Fountain. As it is one of the very rare discussions of Morgan in that decade, we reprint it here. It is curious to see how Bayley on the one hand genuinely recognises the sheer quality of Morgan's writing yet on the other hand seems mesmerised by issues of social class. Still, it is heartening to see this early sign of the Morgan renaissance.

Upper-Class Contemplative

John Bayley

· The Fountain by Charles Morgan

Boydell, 434 pp, £4.95, November 1984, ISBN 0 85115 237 6

There is a category of novel – The Constant Nymph, The White Hotel, Love Story – which is read by everyone for a while and then sinks into limbo. Have such best-sellers anything in common? Obviously they are not – like War and Peace, say – hardy perennials. Their appeal is to something specific in the temper of the time. Going with that, perhaps, is a capacity to have their cake and eat it, and to give their readers the same treat. In Margaret Kennedy’s novel the constant nymph is both satisfyingly bohemian and reassuringly respectable – a combination appealing to the period. She is constant because she dies, and virtuous because she dies a virgin, thus releasing her paramour (and the reader) for further adventures combined with a beautiful memory.Love Story takes the formula a stage further by giving the couple a full and perfect sex-life before the heroine dies, thus releasing etc. As might be expected, the process is more subtle and more comprehensive in such a case as The White Hotel, a more ambitious and imaginative affair. But something similar is going on, enabling the reader to enjoy at the same time the authority and dignity of Freud and the pleasures of pornographic daydream, which combine to license and disinfect the genuine and disgusting horrors of a mass extermination. It seems typical of the literary appetite of our time that the three go together, and that the first two enable art to obtain a sort of false grip on the third, a grip that the Polish poet Herbert says, in his poem ‘The Pebble’, that art should never try to obtain.

In these cases, appetite soon sickens. The succeeding age is indifferent to what had pleased the former, or it protects itself from a touch of pudeur with amusement or derision. Granted that the examples are different, they all provoke disillusion after the spell has ceased to work. But having the cake and eating it is not the whole story: it could be argued that War and Peace itself does just that, letting the reader share both the excitement of warfare and the calm of a Russian idyll, the experience of both aristocrat and peasant, patriotism and pacifism. Probably all successful art works by having things all ways, but great art appeals to what is continuous in human nature. The interest of superior best-sellers, which flourish and fade, is in detecting why they appeal as they do to the spirit of the age in which they appear.

The Fountain, the novel which made Charles Morgan’s reputation, came out in 1932 and had a very considerable succès d’estime. It was much admired in France, where Morgan still has a solid reputation. Valéry admired it, writing that in Morgan’s novels ‘the song of life is always perceptible,’ that ‘a poet is latent in each of his principal characters,’ and that ‘his prose gives to love, even in the suggested presentment of its physical powers, a universal tenderness.’ All that, we might now be inclined to feel, is just the trouble. Morgan writes like a Frenchman, and the ‘beauty’ of a French style is apt to sound uneasy and false in English. Every sentence is admirably finished, so that a man scratching his head or taking down a book becomes as spiritually significant, in terms of the solid gleam of the prose, as a waterfall shining and occulting in the grounds of a great house. To make everything significant in this way, or poetic, is indeed the object of the fine writing. That a book was ‘beautifully written’ was a great and straight recommendation in the Twenties and Thirties, and The Fountain is written as beautifully as it is possible for a book to be.

But that is only the beginning. The French admired the way in which spirituality was harmoniously allied with adultery and physical passion, an alliance to which a fine French style like Valéry’s can attend with perfect ease and savoir faire. The terms in which he praises Morgan show how much Valéry himself was capable in his style of the higher vulgarity. But in French these things are managed with more chic. An example or two will show what seems to be wrong with Morgan’s prose, as with other fine writing of the period. This is the library of a castle in Holland. ‘Here indeed the hours went by in untroubled calm, there being in old books, as in a country churchyard, so deep and natural an acceptance of mortality, that to handle them and observe their brief passions, their urgent persuasions, now dissipated, now silent, is to perceive that the pressure of time is itself a vanity, a delusion in the great leisure of the spirit.’ Well, yes. But this is not just the aftermath of Walter Pater and Marius the Epicurean. The real trouble is that the words have the deprecatory tone of the well-bred Englishman being serious for a moment. They have the air of making ever so slight an apology for their own sensitivity. A French equivalent of the tone essayed in The Fountain – say, Gide’sLa Porte Etroite – is as vigorous and unself-conscious as the word amour, itsdelicatesse genuinely full-blooded. English cadence cannot manage this without becoming too aware of itself. It has to act the part, as the heroine seems to be acting it here, when she sinks for the first time into the hero’s arms. ‘Desire remained without the terror and anger of desire. Delight shone there, but with a clear, tranquil brilliance. He sprang to his feet, drawing her towards him by both her hands, and so easily did she follow that her hair was lifted from her shoulders by the swiftness of her movement.’ ‘Bravo!’ seems the proper response.

It is worth remembering that the athletics in bed which the modern novel goes in for are beginning today to sound almost as self-consciously enacted: as if there was a gap between what the writer really felt and what he expected language to do for himself and his reader. And yet that is not the case here. Reading the novel, one is convinced that Morgan, no less than D.H. Lawrence, believes exactly what his style says, and this is curiously impressive. The difficulty is that though he may deeply believe it as a man, the style can still sound equivocal because of his well-bred English persona, the image of a spiritual gentleman. His hero and heroine are the victims of the style, instead of really embodying it. As in many one-off best-sellers, class is very important, but by no means in a simple way. Everyone can join in, because by being sensitive, and conscious of the true harmony that should exist between the social and the contemplative tradition, we can all enter ‘a certain aristocracy of the spirit’.

Like many persons born in the professional class, Morgan both resents and admires the higher gentry, but he allows this having-it-both-ways privilege to himself and the reader in a highly unusual manner, which must be the key to the book’s success. Upper-class ideals were in need of a good write-up in 1932. The disillusionment of the war, and the brutal treatment of current specimens of the gentry by Evelyn Waugh and others, had sent their stock very low indeed. The Fountain was the ideal novel for the thoughtful middle class because it unexpectedly reinstated an ideal of gentlemanliness, going with tranquillity and inner confidence, which it portrayed convincingly and with power. In Auden’s ‘low dishonest decade’ the best turned out not to lack all conviction. Identified with English history, particularly the Anglican tradition of the 17th century, the middle class could still inherit and reinvigorate their time-honoured relation with the best in society, and have sexual emancipation as well. At a time of Nazi and Communist as well as many other day dreams and ideals, the atmosphere of the book helped to suggest more civilised alternatives, and it is possible that in our day, dominated as it seems to be by various strains of new conservatism, the book might again be a success. Morgan died in 1967, never having repeated the success of The Fountain, though his reputation was, appropriately enough, high during the war, when he produced two memorable short novels, The Empty Room and The Judge’s Story, and a play scenario about escapers from Europe called The River Line, in which a man of solid integrity and spirituality is mistaken for a traitor and murdered. This has the kind of coldly sentimental drama Morgan is good at. He was a drama critic for many years, and his best scenes have the sense of the stage in them, a sense that is absent in the two rather portentous novels which followed The Fountain, Sparkenbroke and The Voyage. Both are quasi-historical. The latter, an almost motionless work with a typically Morgan heroine, is set in Bordeaux at the time of the phylloxera epidemic. Sparkenbroke is about the life and death of a creative aristocrat.

Lewis Alison, the hero of The Fountain, is with the Naval Brigade defending Antwerp in 1914, and is interned in Holland. This had been Morgan’s own experience, and both he and his hero spent a quiet war on parole at a Dutch castle. Morgan occupied himself chiefly in writing a novel, The Gunroom, about his early experiences as a midshipman in the Navy. He lost the manuscript of this when the ship on which he was returning to England was mined, but rewrote it for publication in 1919. Lewis Alison occupies himself with writing ‘a history of the contemplative life’, but he also falls in love with Julie, stepdaughter of the Baron who owns the castle. He has known Julie in her childhood, when her mother, the Baron’s second wife, was married to an English essayist. Julie herself is married to a Prussian aristocrat, Rupert Von Narwitz.

The deceptive leisure of Morgan’s style is good at the suggesting atmosphere of a place like the castle, its routines and rhythms; and he possesses the gift – rare in the English novel though common in the French – for discussing intellectual and religious questions without any striving for effect, weaving them naturally into the texture of our growing intimacy with his characters. This goes with the fact that we come after a time to accept the style as natural, and to take a placid pleasure in its peculiar dignity of self-consciousness, so that there seems nothing absurd in a chapter which begins: ‘Lewis spent the morning in the 17th century, a noble period in Holland, and in England, he was inclined to think, of all periods the greatest.’ Morgan performs the feat, an exceptionally hard one, of drawing us hypnotically into the absorption of his hero, so that the account of his daily working and thinking gives the reader a kind of sensuous pleasure, as if he were doing it too, but without the effort. He achieves the same effect in The Judge’s Story, where the hero is planning to write a book about ancient Athens. The work or the talents of a character in a novel are usually a token affair: the leading function of Morgan’s hero, qua hero, is his dedication to a job and his ability to do it.

The hero’s absorption in his own thoughts and projects is an internal parallel, of course, to the novelist’s attempt to absorb the reader completely into the world of his novel. A striking feature of The Fountain is the way in which Morgan’s success at this seems equivocal, perhaps even to himself. A theme is the need for everyone of integrity to have a quiet place inside themselves into which they can withdraw, and which can never be violated from outside. In their secret enchantment at the castle the lovers possess this temporarily, but the war will come to an end: they will have to make the unromantic practical decision to get married and to settle into suburbia at home. The Adam and Eve by Rubens and Breughel at the Hague is introduced to underline the fact that the lovers and their admiring audience of readers are alike to be ejected from the novel’s Eden.

The instrument of eviction in the plot is Julie’s husband, Von Narwitz. Wounded many times in the war, he arrives at the castle an incurable invalid. He and Lewis take to one another immediately, and have long philosophical discussions. Narwitz is in constant pain, which the novel makes extraordinarily real to the reader, as it makes real Lewis’s own rhythm of meditation in his solitary studies. Narwitz is part scapegoat and part Archangel Gabriel, warning the lovers and instructing them. He is also a good German, a characteristic figure in post-war, pre-Hitler, intellectual England. Though the novel is only indirectly political, it suggests that thoughtful aristocrats everywhere, whether socially or of the spirit, must think and work together; and that former enemies may feel a special sympathy here. ‘I am the enemy you killed, my friend.’ Narwitz’s favourite novel (and Morgan’s too) is Turgenev’s On the Eve. Social and spiritual enlightenment can only be international. Remarkably, there is nothing facile or romantic about Narwitz as high-born Socratic German, nor in his role of forgiving omniscient husband. He dies on the day of the Armistice, and his death is as genuinely moving as the coming together of the lovers.

Morgan was never afraid of strong simple effects, and this might endear him to new readers at a time when the novel may be turning away from its preoccupation with ‘fictiveness’ and its avoidance of direct emotion. At the same time he seems to be under no illusion about the nature of his wartime experience in Holland, which inspired his book. In her thoughtful introduction Leonée Ormond quotes his words on his internment having been a ‘blessing’, a gift of God which ‘compelled me to discover what I deeply cared for in life’. But it was also, at least for his earlier self, ‘a life within life – a sort of spiritual island, and so a delusion’. The difference indicates the way in which novels, as part of their success as an art form, can have things both ways. They know we live in worlds of make-believe, to which they minister, but they can also find these in, and explore their relation to, the unsanctified monotony of life. In his epigraph to the novel Morgan neatly snips out the first phrase of a couplet from Coleridge’s ‘Dejection’ Ode:

from outward forms to win

The passion and the life, whose fountains are within

Coleridge’s couplet in fact begins ‘I cannot hope ...’ But this novel can and does hope. Its wish-fulfilment mechanism, unobtrusively strong, ensures its success in the genre of novels which give us what we want, even though we did not know we wanted it. A propos of the Rubens picture the narrator observes that works of art help to build our retreat, our ‘intact island, ringed with the waters of the spirit’, where we can ‘set out on our own voyages’. Art’s chief function is the higher escapism, and Morgan’s novel subtly and not ignobly acknowledges this and embodies it.

Morgan and T.S. Eliot were fellow Kensingtonians and clearly had a great deal in common. The spirituality of Four Quartets, combining grave withdrawn delicacy with a remarkable power of commanding instant middlebrow popularity, has much in common with that of The Fountain, even down to that embarrassing description of ‘style’ in ‘Little Gidding’, which in its approval of ‘every phrase and sentence that is right’, and of ‘the word neither diffident nor ostentatious’, gives all too good an impression of Morgan’s own way of writing. They were fellow connoisseurs of J.H. Shorthouse’s novel John lnglesant, often mentioned in Morgan’s novels, of the Nicholas Ferrar community, of the moment

while the light fails

On a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel ...

Eliot, we know, read The Fountain with enthusiasm, and there is a strong echo in ‘Little Gidding’ of Von Narwitz’s discourse to the lovers, in which he distinguishes between detachment and indifference, ‘conditions which’, as Eliot writes, ‘often look alike/Yet differ completely’. Spirituality has, inevitably, an equally ambiguous nature, and there are moments when both The Fountain and Four Quartets may strike the reader as having it both ways, serving with fastidious skill both the world and the spirit, and earning the applause of the bourgeoisie in so doing. But that is not an achievement to be despised. It is how good art and best-sellers alike get produced, and in detecting the difference we ought also to recognise the similarity.

This review first appeared in the London Review of Books, vol. 7 no. 2 (7 February 1985)

- In October 2011 the Jermyn St. Theatre in London presented a production of CM's The River Line. In case you missed it, here are three reviews.

Here is what The Times (Libby Purves) had to say:

Charles Morgan was once an acclaimed author and Times drama critic, though too earnest for some: his obituary said that “beauty of diction, dignity of thought, fineness of intuition” do not add up to “the throb of life”. One critic called this 1952 work “so dignified it hurts”. Morgan sadly wrote: “The sense of humour by which we are ruled avoids emotion, vision and grandeur of spirit as a weevil avoids the sun”. Under Anthony Biggs’s direction, this marvellous play demonstrates how seriousness, too, can thrill, particularly when teamed with a tense wartime tale.

Revelations unpeel right to the final minutes, entwined with profound reflections on war, duty, love and death. The first and third acts are set in a postwar country house as Julian and his French wife, Marie, welcome Philip, an American who hid with him in Marie’s granary four years earlier while her Resistance group organised their escape. That ended in a dark, necessary deed, which even now the couple cannot discuss: “We love each other across the silences.” Philip, however, wants to tell his new girlfriend everything.

That past unfolds in the middle act, transporting us to a claustrophobic loft where the men hide with the charismatic officer “Heron” and a nervous young pilot. One of them may be a German infiltrator. We see their preoccupation with leaving no traces, burning papers and disguising the common bowl and spoons as dusty junk: the irony is that the mental scars will not so easily be erased. Back in 1947, the play ends with the difficult acceptance that, as Marie says, each of them “bore their responsibility in the predicament of the world . . . A man does not have to be base to be your enemy”. Its glory is that the fascination of Heron is not because of his fate, but who he was: a rare spirit of luminous serenity. And, as Julian says, this is “a world of lonely animals . . . a desert, until we build ourselves a roof”. The roof is love.

All the performances are good, especially Lyne Renée as Marie: steely and professional in the Resistance, restrained and wise in 1947. Lydia Rose Bewley, of The Inbetweeners, plays Philip’s girl too much on one note, but handles a difficult final soliloquy with heartshaking sincerity. Morgan’s credo resonates: a desire to “see in every face/ An innocent interior grace”.

And The Independent (Paul Taylor) said:

Here is the kind of rediscovery at which Jermyn Street Theatre excels. Once renowned as a novelist and a playwright and for 15 years the chief theatre critic of The Times, Charles Morgan is no longer a name to conjure with. But Anthony Biggs's deeply absorbing revival of his forgotten 1952 play, The River Line, makes a strong case for its morally searching power and beauty and could help put this author back on the map.

Beginning and ending in a Gloucestershire country house in 1947, the piece wrestles with the ethical and spiritual implications of a devastating decision taken under extreme pressure in Occupied France during the war. Some reviewers of the original production scoffingly implied that the piece has the air of a bizarre John Buchan/T S Eliot collaboration in which a mini-thriller is sandwiched between bouts of over-rarefied philosophising on the subject of guilt and expiation. But Biggs and his fine cast demonstrate that the troubled soul-searching in the outer acts is, in its subtle, speculative way, just as intense and momentous as the fateful events in the central flashback to 1943. Here, hiding from the Nazis in a cramped granary near Toulouse, a group of Allied servicemen begin to suspect that one of their number is a German spy.

The figure whose spirit mountingly haunts the play is the charismatic young officer and poet, Heron (portrayed somewhat gauchely by Charlie Bewley of the Twilight films). Morgan clearly reveres this character for his gently inspiring serenity and the glowing way he embodies the injunction in the play's epigraph: "We must act like men who have the enemy at their gates, and at the same time like men who are working for eternity".

That double perspective on life informs the play's increasingly mystical conception of responsibility and atonement. A stoic acceptance that we each have to bear our flawed "responsibility in the predicament of the world" is the hard-won, pragmatic wisdom articulated by Lyne Renee's piercing Marie, the French woman who ran the Resistance group. But Philip, the former GI, who is played with a wonderfully compelling emotional transparency by Edmund Kingsley, comes to take the Greek tragedy view that even the sins we commit innocently or ignorantly demand expiation. Only the dead, though, have the right to forgive. Lydia Rose Bewley performs the climactic speech, where Heron communicates through her, with a quiet, shattering ardour that, like the play itself, puts you in profoundly persuasive contact with the operations of grace.

And here is our review:

WARNING: THEATRE FOR ADULTS

Having lived with the works, including the plays, of Charles Morgan for over half a century, I was not sure that his dramatic creations would actually work in theatre, still less in the 21st century. When I heard that a small London group, the Jermyn Street Theatre, was taking the plunge and producing the dramatic version of The River Line (1949: previously written as a novel), I was both excited and nervous. Could present-day English actors still incarnate those characters from another age, another England? Could modern audiences sympathise? However, it was not something to be missed; and accordingly I flew from the South of France to London to attend the first preview, on October 4th.

(Imagine how nervous one feels in writing a review of a play by Charles Morgan, the man who as drama critic of the Times reviewed more plays than most of us will see in a lifetime, and did so with keen understanding and in impeccable prose.)

Let me say at once that I spent considerable time, in the interval and afterwards, congratulating director Anthony Biggs and producer Richard Darbourne. They have done an astonishing job, with a roughly 24' x 12' stage in a theatre with 70 seats: they have managed to bring Morgan's characters, his plot and his dialogue vividly alive, to make a full house of adults think and feel in equal proportions, and to inspire a group of talented actors with the play's nervous, intellectual and emotional energy so that the production crackles with human electricity.

The actors, of course, are the ones who actually do it. (The Bewleys, as Web announcements show, were a coup of useful publicity for the producers: whether they are right for this play is another story -- see below.) Christopher Fulford, as Commander Julian Wyburton, while not the tall, commanding figure Morgan surely imagined, is one of the stars of the production. With the power of the unsaid that Anthony Hopkins displayed in 'The Remains of the Day', he combines both an emotional depth and what Morgan would have been happy to see called an essential Englishness that is not only convincing but genuinely moving.

The play's other star is Belgian actress Lyne Renée who, as Marie Chassaigne the French former Resistance agent and postwar wife of Julian, is nothing short of miraculous. I did not think it possible so perfectly, in 2011, to create the physical persona of a 1940s woman -- almost all the attempted imitations ring false. Renée is flawless. Not only that, her emotional range is nothing short of awesome; and all by herself she gives the lie to the criticism I have read here and there that Morgan never created real women, that all his female characters are shadowy male projections. Here is Mme Renée to prove them wrong. From now on I will involuntarily see her face in many of Morgan's women, beginning with the wonderful Thérèse Despreux in The Voyage.

Edmund Kingsley plays Philip Sturges, a young American and very much the foreigner in the group. He does it so well, and so sympathetically, that he reminded me irresistibly of a real American college professor of my acquaintance. If he can remind himself that he is on a tiny stage in a tiny theatre and mute his performance to chamber music, he will be superb. (Someone said to me, 'Yes, but that's the way Americans come over to the British'. True; but Mr Kingsley does his American so well that the effect would be created at 2/3 of the volume.)

A surprising treat is Alex Felton as Dick Frewer. Frewer is in many ways a minor character, young, naive, puppyish in some ways, and a foil for the chief wartime character known as Heron. Yet Felton catches with a rare perfection the mixture of naiveté and perceptiveness, of intensity and inarticulateness, that Morgan gave Frewer, and the real charm and pluck of a now partly vanished public-school type.

'Heron', the beautiful, fascinating, inspiring young officer at the core of the wartime scenes, and in a way the core of the whole play, is played by Charlie Bewley. He certainly has the good looks the part needs, though neither his profile nor his legs might perhaps make people instinctively call him Heron. If he can tense up the performance of that difficult part (it's hard to play without the slightest self-consciousness someone everyone falls for), perhaps by rereading Morgan's long description of Heron in the play's preface; realise that much of it is not explained till the last scene; if he can recapture some of the crisp and tense verbal accent of the time (what is now grossly and wrongly dismissed as 'posh'); and if he can make his lazy good looks work in what is literally a life-and-death situation, he will make a good Heron.

Lydia Rose Bewley, his sister, plays Valerie Barton, the young woman Philip Sturges falls in love with. When she first comes on we are visually startled, if only by her costume, and this continues throughout the play. Her bright red hair hangs loose like a Renaissance Magdalen's and she is given awkwardly short jackets and awkwardly short skirts that neither flatter nor give a period look. If she could get a hairdo as 1940s as Marie, and be dressed in something loose, draped and flattering, she would be stunning. Her accent is marginally better than Heron's, and her voice is a genuinely lovely instrument, much at its best when used with clarity, emphasis and power. She has some of the play's most important lines, and she is on the edge of mastering them. If she can forget all dailyness, all simple chat, and be completely the magical, oddly mystical character the author has given her, she might just push the production over the edge into greatness.

Eileen Page as Mrs Muriven and Dave Hill as Pierre Chassaigne, Marie's father, both remind us happily that there is no such thing as a minor part: they play their supporting roles with authority and charm.

The River Line is, like Morgan's two other plays, theatre for adults. For adults who, while loving the stage, need neither spectacle nor irony; who are also literate and thoughtful; and who enjoy being engaged in those capacities by actors collaborating with, and lending living voices to, an author's urgent conversation with his audience. The play's original preface is a short essay 'On Transcending the Age of Violence'. Such a title, from 1949, may provoke a melancholy and ironic smile in 2011; but in it Morgan explains movingly the origins and the development of the play and of the novel that was, as he says, in effect a study for the play. He also dwells on the characters, notably Heron, who takes on some of the characteristics of Lewis Alison in The Fountain.

The spectator leaves, thoughtful and moved. Thoughtful about the human condition in all its real adult difficulties and glories; moved by the presentation of that condition by powerful young actors and director inspired by that great writer and man of the theatre, Charles Morgan.

- Seriously Old News: the Catholic Herald's 9 September 1938 review of The Flashing Stream is no longer available as a link, so we have copied it for our readers.

OPPOSE SINGLENESS OF MIND

The Flashing Stream

In this materialist existence, where values are only valuable when they are tangible, one problem beats insistently against the brain. It arises out of the immaterial otherworldliness that is in all of us, which driven back beyond its frontiers, takes its oppression hardly. But should it press too far forward, how reconcile it with even the highest standards of the outer world? How, in other words, can the spiritual man live harnessed to the secular man? Keep in touch with common things and dream of those quite uncommon?

The artist has his own philosophy and it so often removes him continents away from his fellows. The mystic has found a life which is satisfactory but that sometimes removes him also to contemplative heights that pedestrian man does not ascend. And the problem presses – what is there for those not poets, not given visions?

It seems the great achievement of Charles Morgan (and it is the Morgan motif recurring throughout his work) that he has found spiritual reality for the ordinary man, and has released him in the same way as religion releases a man from the dead dull weight of materialist conception of life.

In The Flashing Stream Mr Morgan points to the release that comes to those of single mind, those that can lose themselves in any ‘impersonal passion’, in his own words.

‘Many are persuaded by despair that against the violence of the contemporary world there is no remedy but to escape or to destroy; but there is another within the reach of all --of a woman at her cradle, of a man of science at his instruments, of a seaman at his wheel, of a ploughman at his furrow, of young and old when they love and when they worship – the remedy of a single mind, active, passionate and steadfast, which has upheld the spirit of man through many tyrannies and shall uphold it still.

‘This singleness of mind, called by Jesus purity of heart, the genius of love, of science and of faith, resembles in the confused landscape of experience a flashing stream, fierce and unswerving as the zeal of saints to which the few who see it commit themselves absolutely. They are called “fanatics”, and indeed they are not easily patient of those who would turn them aside, but, amid the confusions of policy, the adventure of being man and woman is continues in them. . .’

And side by side with the ‘impersonal passion’ of Commander Edward Ferrers R.N., for his mathematics and his invention of anti-aircraft ‘scorpions’, is his adventure of being man, and of Karen Selby of being woman as well as being mathematical genius. To Mr Morgan the two passions interlock, and there is no question, as in many other philosophical plays, of the so-designated love-interest being a pleat put into the fabric of the play to give greater width of appeal to an assorted audience.

Nothing essential appertaining to any side of life is treated as an insertion in Mr Morgan’s work. The great humanism which inspires everything he writes inspires even a modern West-End play with all its necessary and sometimes tiresome conventions is a synthesis built to include all experience. Things that Mr Morgan is doing for the ordinary of today is [sic] exactly what the medieval Church did for the world of another time. It also gave a synthesis of life’s experience, made life an ecstatic adventure, a positive thing intensely valuable in itself, with an explanation and a completion in a great burst of individuality in a world to follow.

In these days of split Christianity, the searching world feels that religion has become blunted. Most sects of today represent life without any exhilaration, as a negative series of do-nots and cannots, with only dubious compensation in an uncertain next world.

The virile and absolutely “pro-life” Christian humanism of St Thomas Aquinas, which gave dignity and excitement and logic to this temporary existence, has been largely lost outside the Catholic Church. Is it surprising that those who have not found the synthesis they need in other religions should hardly dare to hope for it in yet another religion such as Catholicism, and therefore they turn to the holiness of the imagination – to the modern philosophical novel such as that of Charles Morgan?

With such other points of completely absorbing interest to discuss, it is nearly possible to forget the work of even a magnificent cast as that of The Flashing Stream. Margaret Rawlings, as the woman capable of the impersonal as well as the personal passion, gave perhaps her greatest performance yet, in a part which fits round her like a glove. Godfrey Tearle, a little less successful, spoke and moved like one living within the character of the philosopher-naval commander and never lost his common touch in his unreserved devotion to mathematics and the project.

The Flashing Stream can never be recommended just as a play to be seen – but only as an experience that the imagination can live in.

Iris Conlay

- Seriously Old News: here is Mordaunt Hall's August 31, 1934 New York Times review of The Fountain in the RKO movie version of that year, directed by John Cromwell and starring Ann Harding, Brian Aherne and Paul Lukas:

If the cinematic transcription of Charles Morgan's novel, "The Fountain," which is now at the Radio City Music Hall, leaves much to be desired in the matter of drama, it is by no means a picture to dismiss lightly. For, in the first place, it has been handled for the most part with noteworthy reverence for the author's work. Also it is beautifully photographed and has A highly efficient and well-chosen cast and carefully designed settings. And although it is weak in drama and strong on words, the dialogue is written persuasively. It is one of those intelligent offerings which one is apt to regret criticizing adversely. To call it dull, seems too harsh, and yet some persons may find it so.

Except for the depiction of a few incidents, it is dubious whether much more could have been accomplished with the narrative than John Cromwell, the director, and his colleagues have succeeded in doing. The novelty of dealing with British officers interned in Holland during the World War lends no little interest to the film and the presence in the leading rôles of Ann Harding, Brian Aherne and Paul Lukas, compels attention. The introductory scenes lead one to expect something far more exciting than is given. Perhaps, during the tennis match between Lewis Alison and Ballater, the announcement of the German reports of the result of the Battle of Jutland might have been set forth more dramatically, but even as it is done it offers much food for thought.

It is an infinitely better vehicle for Miss Harding than several of her previous films. It never sinks to anything tawdry or cheap and Mr. Cromwell has directed his scenes with praiseworthy restraint. Furthermore, the incidents are always plausible. Miss Harding, of course, portrays Julie van Narwitz, the English girl whose husband is a German officer. Soon after the story begins, Julie encounters her childhood chum, Lewis Alison (Mr. Aherne), a British flying officer interned in Holland, who is invited to stay in Julie's stepfather's imposing home. It soon becomes evident that Alison and Julie are in love, but she is not the type of woman to deceive her husband.

Paul Lukas impersonates the crippled Rupert van Narwitz, who, after he appears at the van Leyden home, obviously becomes aware that his wife is in love with the young Englishman. Mr. Lukas's performance is affectingly sympathetic. The contrast between the one-armed victim of poison gas and the fortunate Alison is drawn with no little subtlety. Miss Harding gives a definite and sincere characterization of the earnest young wife, who, notwithstanding her love for Alison, does everything within her power to help her husband regain his health. The shock he suffers on learning of incidents at the close of the war, however, is partly responsible for Rupert von Narwitz's death.

Jean Hersholt gives an admirable portrait of Baron van Leyden, Julie's stepfather, and Violet Kemble Cooper is gratifyingly natural as her mother. Mr. Aherne is splendid as Alison and Ralph Forbes does well as Ballater. Among others in the cast who distinguish themselves are Sara Haden, Frank Reicher, Charles McNaughton, William Stack and J. M. Kerrigan.

An excellent Technicolor short subject entitled "La Cucaracha," in which the featured players are Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado and Paul Porcasi, shares the screen with "The Fountain." The color designs are credited to Robert Edmond Jones, and the effect on the screen is charming. The little tale is laid in Mexico and it offers dancing, music, a gleam of drama and touches of comedy.

The chief item on the stage program is "Little Old New York," with Joe Jackson, Mildred Gerber, Red Donahue, George Meyer, the Rockettes and the ballet corps.

THE FOUNTAIN, adapted from Charles Morgan's novel; directed by John Cromwell; a RKO-Radio production. At the Radio City Music Hall.

Julie . . . . . Ann Harding

Lewis Alison . . . . . Brian Aherne

Rupert . . . . . Paul Lukas

Baron van Leyden . . . . . Jean Hersholt

Ballater . . . . . Ralph Forbes

Baroness van Leyden . . . . . Violet Kemble Cooper

Sophie . . . . . Sara Haden

Allard van Leyden . . . . . Richard Abbott

Goof's Wife . . . . . Barbara Barondess

Goof van Leyden . . . . . Rudolph Amendt

Allard's Wife . . . . . Betty Alden

Van Arkel . . . . . Ian Wolfe

De Greve . . . . . Douglas Wood

Doctor . . . . . Frank Reicher

Nurse . . . . . Ferike Boros

Commandant . . . . . William Stack

Kerstholt . . . . . Christian Rub

Shordley . . . . . J. M. Kerrigan

Lampman . . . . . Charles McNaughton

Willett . . . . . Desmond Roberts